Ricky Martin would like to make one thing completely clear. The show he is bringing to London this month is "erotic", he says, leaning towards me. "Very erotic," he lowers his voice meaningfully.

There'll be fetish play, whips, chains, nudity (on film), he tells me, and an onstage orgy involving him and his eight dancers. He predicts the 18,000-strong audience will want to join in. And it's this that worries me. When I go to his Madrid show the next day, the temperature outside is 33C. Inside, in a stadium heaving with heavily perfumed women and heavily muscled men, the temperature is anyone's guess. When the fiftysomething woman beside me stands up, howling, at Martin's first appearance, a slug of her sweat hits me, and I suck my teeth nervously. It's a bacterial breeding ground, I think. When this orgy gets under way, veruccas will be spreading like wildfire.

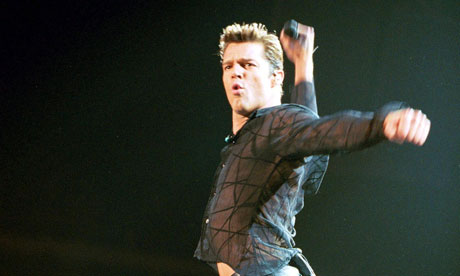

But I needn't worry. The show is less erotic, more exuberant. Martin bounds around the stage like a huge, horny chipmunk, thrusting, hopping and swaying through the daffy charms of Shake Your Bon-Bon and She Bangs. There is a sweetness about him, a yearning for approval, that recalls his boyband childhood, and his enormous success in the late 1990s; when he sings the lyric "I wanna be your lover" and mimes holding a massive phallus, eyes astonished, then beseeching, it calls to mind nothing so much as a child proffering a large frog. The crowd screams when he opens his shirt, they punch the air to his 1998 football anthem La Copa de la Vida, and lose it when he sings his recent Spanish language release Más. As the gig ends, Martin gazes out at the audience, sweaty with joy.

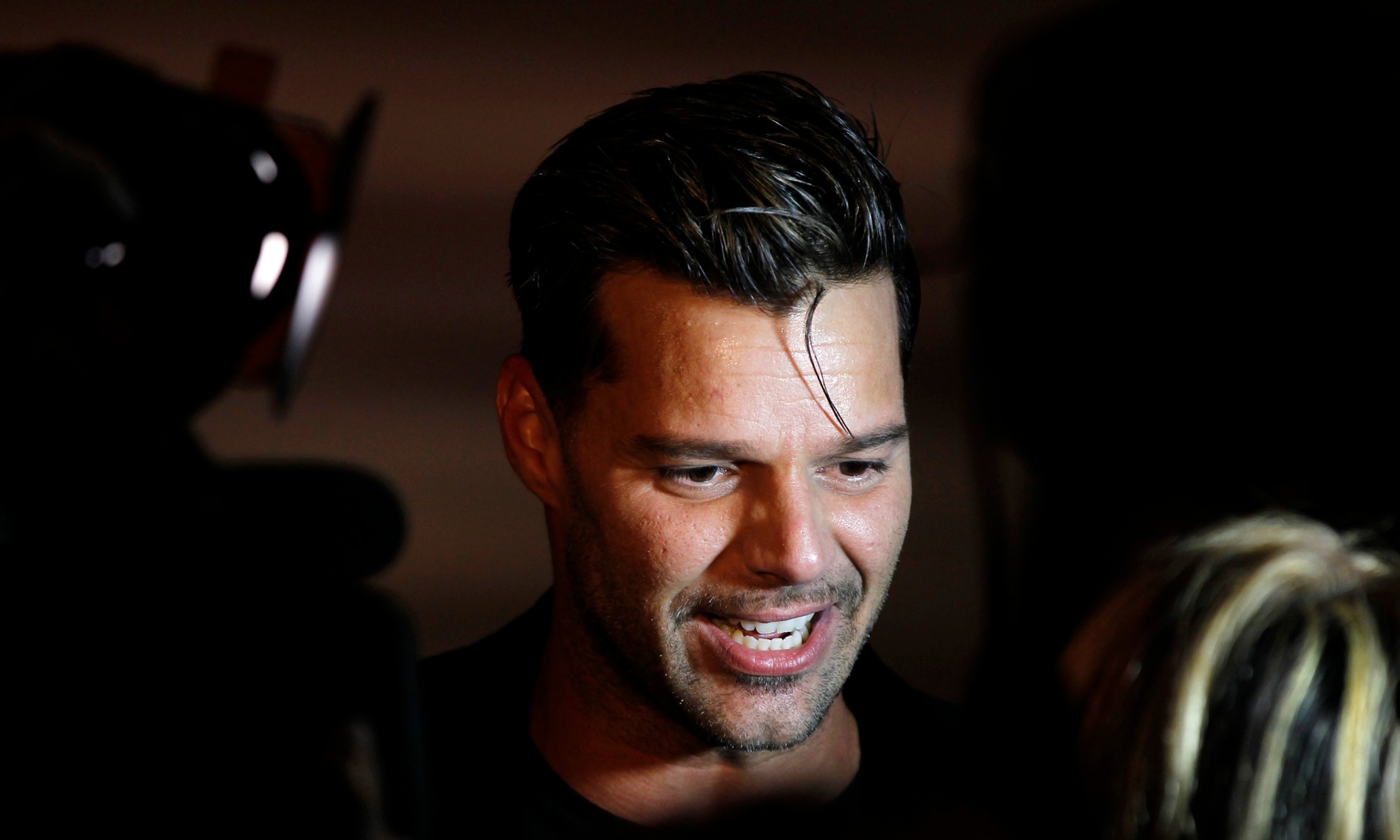

These are ecstatic times for him. Last year, after more than a decade of rumours and sniping about his sexuality, Martin announced online that he was "a fortunate homosexual man"; he followed this statement with his autobiography, Me, in which he described his sheer pride and relief at coming out. For this, his first UK newspaper interview since the announcement, we meet in a hotel suite in Madrid, and he is warm and open, all hugs, as are his entourage of family and lifelong friends. When I ask whether he still feels as euphoric as he did while writing the book, he sprawls on the couch, and starts running his hands wildly over his chest. He is the most physically expansive person I've ever interviewed. "I feel liberated," he laughs. "I feel in touch with myself."

Then he sits up, suddenly serious. "I feel protected. I don't feel alone. Because sometimes when you're quiet about yourself, you feel all alone. And all of a sudden you come out and you have this amazing community, the LGBT community, and LGBT-friendly people, who are giving you nothing but love. And if I focus on this, I get tears in my eyes, because, oh my God, I wish everyone that was struggling right now could feel what I'm feeling as I'm talking to you. It's just love coming from every fucking direction!"

This is particularly poignant for Martin because of the years spent dodging questions and insinuations. The most notable incident was when Barbara Walters, the veteran US journalist, interviewed him for an Oscars special in 2000, and badgered him to address the rumours. (She has since said those questions were "inappropriate", the one regret in her three decades of Oscar interviews.) He replied that "sexuality and homosexuality should not be a problem for anybody" and refused to say much more; back then, he was terrified of what would happen if he came out, the possible rejection. "I hated it when people tried to force me out when I wasn't ready," he says. "It was very painful, and it actually pushed me away from doing so." The salacious tone of the coverage only made him more convinced that people would react badly when he did.

At 39, it's clear he's spent much of his life trying to understand and control his sexuality. "If I had spent a quarter of the time that I spent manipulating my sexuality in front of a piano instead, I would be the most gifted piano player of my lifetime," he says. "What people were expecting from me was not who I was, and I forced myself to believe that what they wanted could be my truth, my reality, and I went after it hardcore. What I'm trying to say is this: I don't think I was lying . . . I would have my flings [with men], and I would think, OK, maybe I'm bisexual, but then, no – because I can be with a girl, and it feels amazing." In his book, Me, he seems genuinely smitten when he writes about his female lovers. He writes of one that "she hated her breasts, but they made me crazy. I loved looking at her body; it was like a painting that I could describe to the last detail. Her legs and the little toes on her feet lit me up. I wanted to devour them – and I always did."

And so these feelings made him think, "I'm not gay," he says. "And you would watch TV, and you would see this caricature of someone who's in the LGBT community and you'd say, 'Well, I'm definitely not that.' And then you start convincing yourself, or trying to prove to yourself, that you're not gay. If you add to that the amount of success I was having," he pounds his fist against his palm, "I'm singing La Vida Loca and enjoying it and being successful and accepted, and I thought, let's keep pushing towards this, because who's not seduced by acceptance?"

Martin's early life, particularly his years in the boy band Menudo, would probably have confused any gay child. He grew up in Puerto Rico, the only child of psychologist Enrique Martin and accountant Nereida Morales; his parents split up when he was two, and both had children with other partners, but doted on him. At just three or four, he realised he had an attraction "to my friends, to the same sex – I felt something really magnetic about boys. And then I thought, no, I'm not supposed to be feeling this.' But it was very powerful." He was Catholic, believed in the church's teachings, and loved being an altar boy. "I thought, I'm supposed to like girls, because that's what the church says, and that's what my priest told me . . . Unfortunately, according to my faith, what I was feeling was evil, and I struggled."

He always wanted to be in the spotlight, and at nine he started appearing in TV commercials; by 10, in the early 80s, he wanted nothing more than to join Menudo. The band had released their first album in 1977, and had a distinctive structure – when members hit their 16th birthday they would be replaced by someone new. At his first couple of auditions he was too short. But when he was 12, he was accepted, and early the next morning was on his way to the band's base in Orlando, Florida, to start a new life. His job, from now on, was to be appealing to girls.

In his autobiography, Martin says Menudo cost him his childhood, but he equivocates slightly now. "A child is a child, no matter what," he says. "But I became a rock'n'roll star slash sex symbol at a very young age. I was thinking: what do I have to do to get the attention of the girls? It was my job to move my hips, because then they scream, and that meant I was successful, like the rest of the guys. Was I ready for that? I don't know. But that's what I was supposed to go through, according to my karma." (Martin no longer follows a specific religion – he has a T-shirt that reads "God is too big to fit in one religion" – but he refers to his spiritual beliefs passionately and often. His autobiography begins with a quote from Gandhi, and is sprinkled liberally with references to yoga and swamis, which can be hard to take seriously. At one point in our interview he says: "Buddhism has a very beautiful teaching that says the worst thing you can do to your soul is to tell someone their faith is wrong." His eyes widen with awe. "And when I heard that I was like: 'Oooh! That's a tweet!'")

He says he was 13 "when this obsession with being accepted kicked in. You needed to say yes, because if you said yes, the girls liked you, the girls screamed, and the media would talk about you. I was travelling all over the world, and I had girls following me, private jets, private suites. You would look out of the window and you would have thousands of people . . ." He throws his arms in the air, mimes screaming wildly. The media called it Menuditis. Sounds painful, I say. "Like meningitis!" he laughs.

Martin was in the band for five years, and then went to live in New York, where he spent a lot of time sitting on park benches, exhausted and reflective. But he was soon appearing in a musical in Mexico, then a soap opera, and at 18 he signed a contract with Sony Music and began making Spanish language albums. He played a singing bartender on the US soap General Hospital, and by the late 1990s he had an enormous hit with World Cup anthem La Copa de la Vida (The Cup of Life). It reached No1 in more than 60 countries. This led to a star-making performance at the 1999 Grammy Awards, a duet with Madonna, and the release of his first English-language album, Ricky Martin. The standout track, Livin' La Vida Loca, dominated the summer of 1999 – it was an ear-worm of a song about a wild, superstitious young woman who encourages people to take their clothes off and go dancing in the rain. He was everywhere. The album sold almost 17m copies worldwide, his personal appearances brought Oxford Circus to a halt, it was rumoured his trousers had to be triple-stitched to keep his pelvis-thrusting performances in check and he was the subject of countless drooling interviews about his sex symbol status.

He seemed unstoppable, but the pressure of work, and the media attention surrounding his sexuality, started to feel oppressive. So in the early 2000s, he cancelled a concert in Buenos Aires, and went home. "I didn't like who I was," he writes in Me. "I moped around my house and had very little sense of humour." He describes a friend telling him he was screwed up. He responded by throwing a glass against the wall. Was he depressed? "A doctor never told me that," he says, "so it was not diagnosed. But a lot of people around me were like: 'Oh my God, we lost him . . .' But rather than depression, I think it was a touch of rebellion, you know? It was the first time in 10 years that I was relaxing in my house, waking up when I wanted, watching movies until the sun came out, going to a club if I wanted to. It was the first time in my life I was not dealing with a schedule."

Martin continued to record – Spanish-language albums, and the English-language album, Life, which came out in 2005. But his thoughts were turning to family. He wanted children. And so he said: "OK, what are my options? Am I going to adopt? I just sat in front of the computer, doing research, until I found surrogacy, and I was like: 'Woah! This looks really interesting.' I interviewed so many people that were part of this beautiful world, and I decided this was going to be my way." When he told his mother, "she was like 'surr-o-ga-what? This is like a movie of the future, Rick.' And I replied, 'Well, Mom, we're part of the future.'"

He found an egg donor, and another woman to carry the baby, but it was a closed surrogacy – neither woman knew then, or now, that Martin was the father. In August 2008 his twin boys, Matteo and Valentino, were born. He was determined to look after them without help, until his mother said: "'You're like a zombie.' And I'm like, 'No, I'm noooooooot'" – he pretends to fall asleep, mid-speech – "because I wanted to do it all." He makes a loud snoring noise, and drops his head again. "And that's when I said, 'OK.'"

I ask whether he wants more kids, and he says he'd like "a daddy's girl". He's going to be living in New York next year, playing Che Guevara in Evita on Broadway, and he plans to start the whole process again. "I'll be steady in New York, and then, after I do the play, the baby [will be] born, and I'm going to be able to spend time with her."

It was having his kids that gave Martin the final push to come out; he told Oprah Winfrey last year that he didn't want his family "to be based on lies". Still, when it came to announcing the news, he was seriously nervous. "When I pressed send, I was really scared," he says. "I went to my room, and I was holding my pillow, and three minutes later I called a very good friend and said: 'Tell me what they're saying.' And she's on the other line, crying: 'You don't understand the amount of love you're receiving.'"

He's been in a relationship for almost four years now, and says that he can't believe it. "That was not in my plans – not part of the schedule! His name is Carlos, and he's an amazing human being. He works with the other side of the brain, because he's a financial adviser, a stockbroker." Does he think they'll get married? "It's funny because, you know, we never talked about it, but now the question is coming up [in interviews] all the time. The other day we were reading a magazine and," he mimes them looking at each other, "we were like: 'You're cool with this, right? No pressure?' And I'm like: 'I'm cool, everything is cool.' Not yet. Whenever it's time. I would love the option to marry in my land, my island [Puerto Rico], but unfortunately it's not an option for us yet, which I think is ridiculous. But it's part of a very beautiful process that's happening around the world little by little. Hopefully I will see it, and my kids will see it."

Martin's career will probably never return to its late-90s peak, but it is healthy: he is about to release a new greatest hits collection in the UK, is on a tour that will last until the end of the year and he has 3 million followers on Twitter. Until now, much of his success seems to have been driven by the need to avoid asking himself difficult questions, to keep moving and pushing ahead. Is he still as hungry as ever? "My priorities are different," he says quietly. "My priorities are: I need to be good; I need to be well within for my children to be well within; and then the creative process flows, organically and smoothly. I'm not looking to experience what I went through in the Livin' La Vida Loca days again. Now I just get really turned on by the audience." He pauses significantly. "Really turned on."

07:28

07:28

Unknown

Unknown